|

| Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael, 1483-1520),

'Granduca' Madonna Palazzo Pitti, Florence |

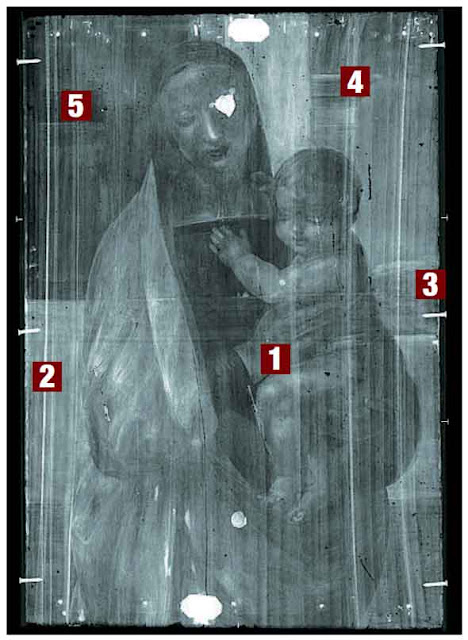

Could a dark, almost black background surrounding the figures of one of Raphael's most famous paintings, the Granduca Madonna in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, change the story of a painter and the way he is researched? And it is possible that an analysis of the panel recently conducted by the OPD (Opificio delle Pietre Dure) in Florence could give a definitive answer to a question that has divided three generations of art historians between two theories: has the black background always existed, or was it added later? Here is the answer in a few words from Marco Ciatti: "The parts painted over the black background are successive retouchings." Is this an opinion? No, it is a certainty, because the X-ray fluorescence analysis, in practice a radiographic procedure that analyses the chemical components of the pigment, shows that the parts painted over the black background and the background itself are not original, but were added later than the Madonna and Child.

But to understand this we need to mention other factors. The Pitti Madonna is one of the last pictures showing Raphael's dialogue with Leonardo da Vinci. What is certain is that in all the Madonnas painted by Raphael in the years around 1505-07 a landscape appears, to mention only the Terranova Madonna in Berlin, the Madonna of the Meadow in Vienna, the Cowper Madonna in the National Gallery in Washington, the Madonna of the Goldfinch in the Uffizi and the Belle Jardinière in the Louvre. There is also a drawing in the Uffizi, which is universally recognised as a study for the Granduca Madonna. In this drawing one can see two things: the painter's initial idea was to paint an ovoid picture, later transformed into a rectangular one; also, in the drawing, unique architectural elements to the left and right are clearly marked. So Raphael envisaged the Pitti Madonna within a space constructed to give breadth and depth to the figures. Moreover the recent X-ray, conducted with new techniques, but preceded by another thirty years ago, has helped define the image painted by Raphael: the interior of a room, a window, perhaps a balustrade, and beyond this, to the right, a landscape. The painting was intended to contain architectural structures like in the Madonna in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, and moreover Raphael, in this period, also painted portraits in an architectural landscape, such as the Lady with a unicorn in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, and the Portrait of a lady in the Louvre, a strongly Leonardo-esque design with a vast landscape background.

| ||

|

| Madonna and Child with St Joseph Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg |

So I think the elimination of the dark background is now required, to reveal the original text, but the question remains: what led to the covering up of Raphael's precious text which, as evidenced by the X -rays, still exists? Some marginal damage? And is the panel itself still intact or, as it seems, has it been cropped? In short, the problems are many; it is certain that we are confronted with a discovery that will forever change the image of the Granduca Madonna, diffused in millions of copies and now seen as almost holy. Think about it: we are about to see disappear forever the only known Raphael that was disguised as a Caravaggio!

Arturo Carlo Quintavalle

(translation: A Curran)

No comments:

Post a Comment