|

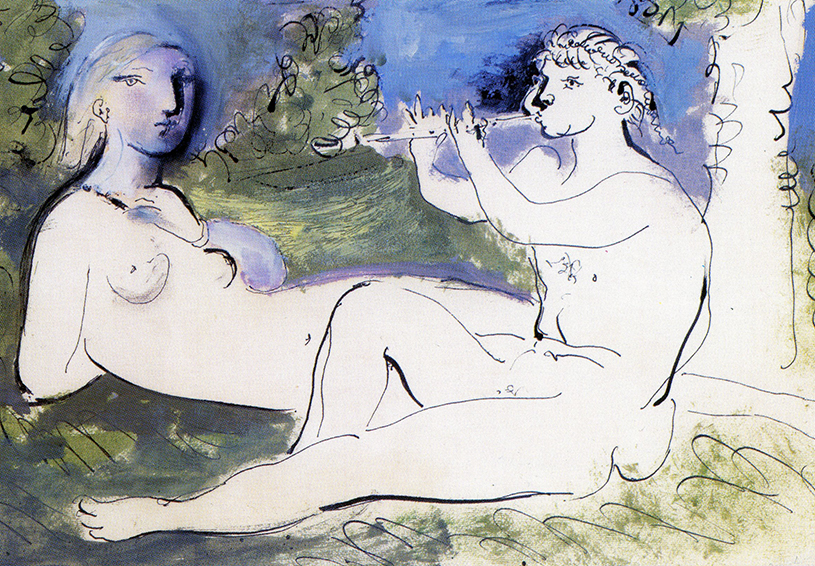

| Picasso, Reclining Nude and Flute Player, 1932 |

(Philippe Sollers in Le Nouvel Observateur, 21st October 2010)

Mention the word 'epicurean' and straightaway a wall of cliches and prejudices gets in the way. By definiton, an 'epicurean' is a grossly sensual person, a sort of prominent provincial bourgeois who thinks only of eating, drinking and making love. This obtuse materialist can see no further than his own body. We have to believe that the philosophy of Epicurus (3rd century B.C.) had, and still has, the effect of an atom bomb from which we must protect ourselves at all costs. A deep thinker in a 'garden'? Someone who reveals to you, with perfect serenity, the nature of things? Who accepts the company of anyone at all regardless of their social background? Who even goes so far as to surround himself with women? Horrors! Read him, and you will understand why all those esteemed systems of thought, like all authorities, have grave reasons to discredit this prophetic vision. Epicurus, Lucretius, two names best avoided.

No-one has been more insulted nor more censored than Epicurus (already Plato burned the books of his precursor Democritus). Those atoms tumbling eternally in the void are abominable. Worse: a small leap aside without cause (the 'clinamen'), and there you have the origin of all that exists, you included. No God the Creator, no Father Big-Bang, no Last Judgement, no Beyond. Nihilism? Not in the least; the glorification of life and of feeling, the negation of death, the justification of pleasure. Thinking and feeling are the same substance, which explains moreover why those who do not think much do not feel much either. Atheism? No, there are in fact gods, but, indestructible and blessed, they live in 'interworlds'. They do not care about humans, but mortals may, through thought, reach them. So this Epicurus thinks he's a god? He even maintains this bravado, this unjustifiable boast. Listen to him, he is clearly in a mess: "Remember that, whilst you have a mortal nature and have limited time, you have risen, thanks to your reasoning on nature, up to the boundless and the eternal, and that you have observed what is, what will be and what has been."

Here, the philosophers let fly: Epicurus (whose works have only partially survived) is scandalous, ignorant, debauched, a thief, a liar, immoral, inebriate, profligate, a plagiarist, a frequenter of prostitutes, a megalomaniac. Christianity will call him a pig, which is to his credit. 'Swine of Epicurus' is a well known epithet. Diogenes Laertius, in his Lives and Doctrines of Eminent Philosophers, thanks to which we can read this great troublemaker, reports these insults, and concludes soberly: "This is what some writers have dared to say about Epicurus, but all these people are mad."

These madmen, apparently normal but with totalitarian powers, wish us to be subject to the fear of death. But: "Become accustomed to the thought that death is nothing to us, since good and evil only exist as feelings. From which it follows that a precise knowledge of this fact that death is nothing to us enables us to enjoy this mortal life, in that it avoids adding to it an idea of eternal life and relieves us of regret for immortality. For there is nothing to fear in life for whomever has understood that there is nothing to fear in no longer living. He who professes to fear death, not because once upon us it is to be feared, but because it is fearful to anticipate it, is a fool." More succinctly: "Necessity is an evil, but it is not necessary to live with necessity."

|

NON FUI. FUI. NON SUM. NON CURO

I was not. I was. I am not. I care not.

(Epicurean gravestone epitaph)

|

Lucretius has unprecedented tones, his certainty is total (we find this same fervour in Dante or Lautréamont) "I walk where none have ever walked, delight at approaching inviolate springs, delight at picking fresh flowers to make my crown." Epicurus has made the light burst from the shadows, he has discovered the world, his writings are "words of gold", thanks to them, the terrors of the soul flee. "I see, across the entire void, all things fulfilled." The power of the gods appears in the forces of immense time, and also the "abodes of peace" appear. This great peace of true thinking, amid the vortices and in the eye of hurricanes, is ultimately a mystery experienced.

In spite of the censorship, Epicurus and Lucretius have entered History. We find them, more or less covertly, in the Renaissance. It is enough to cite the names Montaigne, Molière (who may have translated the De natura), Sade, and, logically, the young Marx. Epicurus today, on a planet invaded by the control of simulacra? We can imagine that he would be an impassive spectator before this deluge of images, and that he would even make a canny and disdainful Faustian pact with illusion. Beyond good and evil, then, like Nietzsche, great admirer of Epicurus. What is The Genealogy of Morals if not a supreme act of emancipation? The Spectacle is nothing, there isn't the least reason to be indignant about it. Let us end with La Fontaine, in this fervent homage to Epicurus:

Pleasure, pleasure, who once was mistress

Of the fairest spirit of Greece

Disdain me not, but stay at my side

For here thou shalt be occupied.

(Translation: A Curran)

Works by Epicurus translated by Robert Drew Hicks (Internet Classics Archive)

Lucretius: On the Nature of Things (De natura rerum) translated by William Ellery Leonard (Internet Classics Archive)

No comments:

Post a Comment